I’ve long argued that we nonprofit communicators can learn a great deal from expert writers and storytellers beyond the borders of the nonprofit world. Today’s post offers insights and advice from a great quartet.

What sets them apart is not only their skill, but also their ability to describe their craft in clear, accessible ways.

Let’s start with a couple of insights from Michael Lewis, author of Liar’s Poker, Moneyball, and Flash Boys among others.

“Unless you have a story, you don’t have a way to persuade people . . . Story organizes your facts into meaning. You can give people all the data in the world. That won’t move them. You’ve got to organize the data into a story.”

We often think of storytelling as a way to evoke emotion and that it certainly is. But Lewis reminds us that story is also fundamental to effectively reaching people with factual information.

When our messages are just a litany of facts, we lose people’s attention. But when we are able to embed those facts in a captivating storyline, we’re on much firmer ground.

Always ask yourself: Am I leading with emotion and then backing it up with fact? And have I located the facts I want to get across in a persuasive story setting?

“If you’re reading it aloud to yourself, you’ll see things and hear things that you just wouldn’t pick up if you were just reading it. You’ll also pick up when there are like boring dead spots where you don’t even want to read it. And it will make you more aware of where it needs work and where it doesn’t.”

Many writers talk about the value of reading your draft out loud. But Lewis is especially articulate on the reasons why it matters. He also makes a related recommendation.

If you’re working on a project, try just telling the story to a friend or colleague. You can judge by their reactions what parts of your story are really connecting and which ones elicit a shrug or a blank stare.

Try it. I bet you’ll find it a helpful way to tighten up and strengthen your messages.

That brings us to another nonfiction writer who centers on investigative reporting, the legendary Bob Woodward.

“For anyone even a very fluid writer, talk the story out to someone. Most people are naturally oral. (So) just sit down and say okay this is what I’ve got.”

Woodward is making a similar, but somewhat different, point than the Lewis one we just examined. With his reminder that “most people are naturally oral.” Woodward makes clear us why reading out loud strengthens our copy.

He’s also suggesting a different role for your collaborator. Most of us tend to ask someone whose judgment we trust to read our draft and tell us what’s working and what’s not. Woodward’s suggesting a conversation might be a better approach with your partner telling you what they hear missing or not landing right. Now, let’s look at an insightful suggestion from the versatile Steve Martin.

“You’re writing something, you think where should it go next? Forget about where it is going. Where should it go? What feels right to you? What’s the next paragraph?”

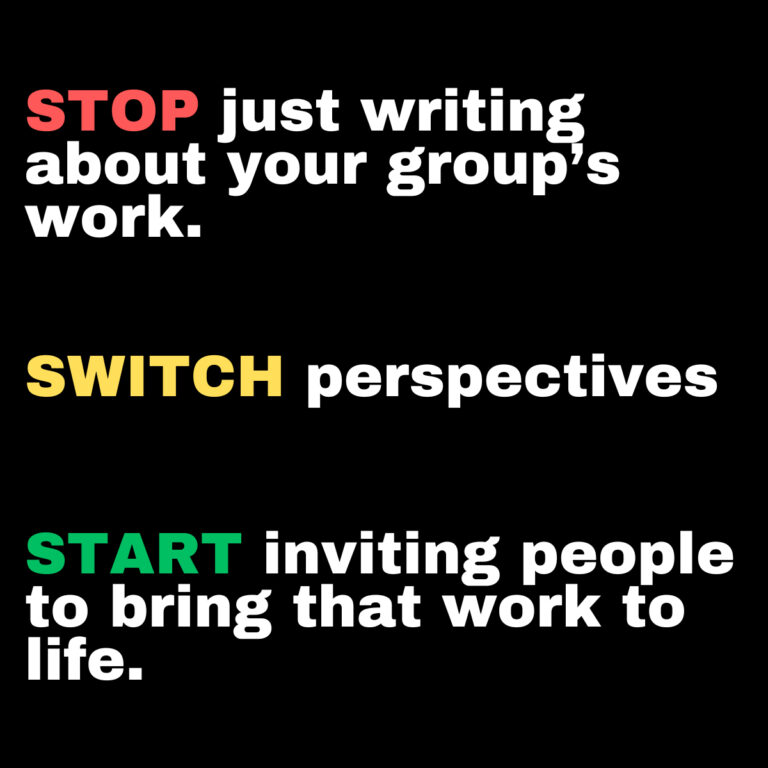

This quote reminds us to be intentional and creative about where we take the message we’re writing. It’s easy to fall into a rote, predictable pattern. When I started out, common advice about how to structure a fundraising letter went like this: Describe the problem/describe the solution/restate the problem/restate the solution/make the ask. Any consistent pattern like that undermines reader interest.

So don’t just thoughtlessly fall into a pattern. Stop and think. What are my options? Where could I take this message next? Which path would engage and surprise my reader? Our brains are trained to predict what’s coming next. When we take an unexpected turn, it heightens the reader’s interest. So be imaginative. Don’t be too predictable.

One final piece of writing advice comes from the amazing television producer and screenwriter Shonda Rhimes. (Side tip: If you haven’t seen The Residence starring Uzo Aduba, check it out.)

“You want a show that has ups and downs and places for people to go emotionally.”

We all know how important it is to lead with emotion. But it’s a little more complicated than that. You have to choose the right emotions to match the moment. And the emotions have to be and feel authentic coming out of the mouth of the person expressing them.

Rhimes reminds us of another critical factor. The emotional arc of our messages has to include variation. If everything is written at a fever pitch, it won’t have nearly the impact of a message that, in Rhimes’ wonderful phrase, gives the reader “places to go emotionally.”

As all of these writers remind us in various ways, craft matters. And the more we learn from master communicators from different fields, the more persuasive our messages will be.