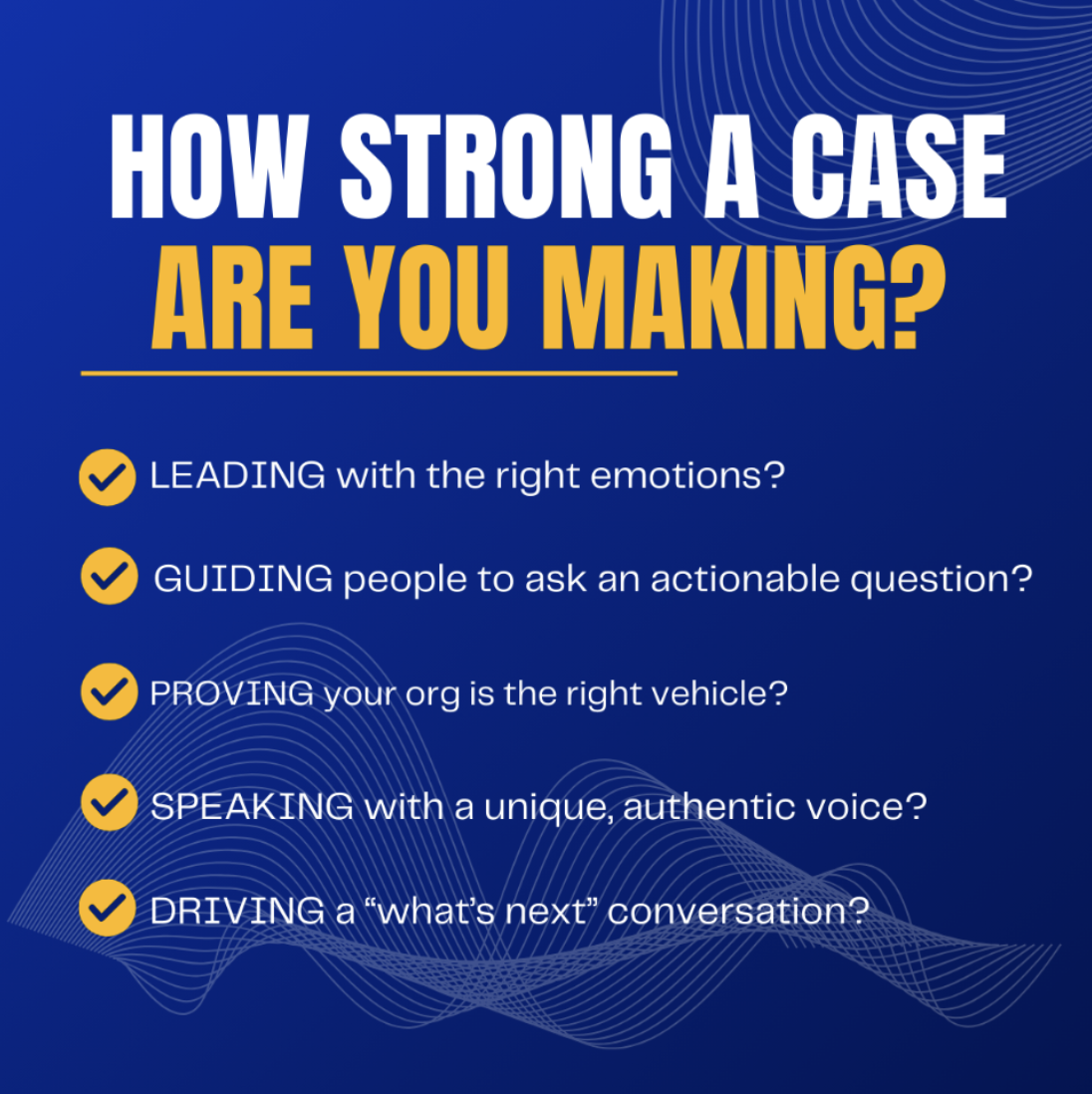

A Five-Part Test

The mad dash from Labor Day to Election Day. The pressure to make the most of Giving Tuesday. The tension of year-end fundraising. Soon they will all be upon us. So now is a great time to make sure you’re making the most persuasive case possible for your cause. Here are five questions to help you re-think, update and strengthen your case for engagement.

Leading with emotions is key. But the real goal is making an emotional connection that both matches the moment and reflects your group’s voice and personality.

Childcare experts talk about helping kids deal with their “big feelings.” Well, however the elections turn out, people you’re messaging are going to have some big feelings of their own. And the strongest messages – political or not – will take those big feelings into account. That doesn’t mean just mirroring how people are feeling. But it does mean taking their emotional state as a starting point.

It’s just as crucial to align your messaging with how your group carries itself in the world. For instance, the World Wildlife Fund can effectively convey “warm and fuzzy” emotions. Not so much the ACLU which people expect to project toughness and determination. Make sure the emotions people understand as your group’s defining ones are front and center in your messaging.

Bottom line: The emotions you invoke have to fit the moment and fit the messenger.

Within limits, how you frame the case you are making can determine whether people find your work actionable and engaging or just too daunting to take on. Which side of that line you end up on can have enormous implications.

Take time to think through what question you are leading people to ask by the way you present your work. Let’s look at a few groups, the more actionable question they guide people to and the more daunting question they avoid centering on.

- Doctors Without Borders leads people to ask “Isn’t it rewarding to support selfless doctors who are delivering emergency medical care to people with nowhere else to turn?” as opposed to “How can we make sure every person in the world has access to the emergency medical care they need?”

- Amnesty International leads people to ask “Isn’t it important to shine a light on human rights abuses and make sure political prisoners know they aren’t alone?” as opposed to “Can we bring an immediate end to human rights abuses across the globe?”

- Habitat for Humanity leads people to ask “Isn’t it great that, in community after community, volunteers come together and help families build and improve places they can call home?” as opposed to “How do we solve the national and global crisis in affordable housing?”

- The ASPCA leads people to ask “How can I help rescue and save vulnerable animals?” as opposed to “Can I help bring animal cruelty to an end once and for all?”

It isn’t that all these organizations don’t wish for and work towards broader, more global

solutions. They just message in ways that avoid that being the yardstick by which they are judged – and by which people think about their own ability to have an impact.

Examine your own case. Think through the question you are leading people to ask – and examine whether prompting a different question would open up a more promising conversation.

Convincing people the problem you are working on is worthy of their personal engagement isn’t enough. You also have demonstrate that your group is the right vehicle for doing so.

Fewer and fewer donors are making “body of work” contributions based on general support for a group’s mission. Most people are acting in a more momentary, utilitarian mode. They select from among a broad number of groups they know and respect, choosing the one best positioned to address their top concern of the moment.

It’s a selection process most easily met by groups that have a “franchise” as the org that comes immediately to mind on a given issue. Think Planned Parenthood on reproductive rights. ACLU on civil liberties. Audubon Society on protecting birds.

But most groups don’t have that inside track position. Take, for example, one of the multitude of environmental groups working on climate change. In situations like that, your case for engagement has to argue not just for the urgency of the issue but for your unique – or, at least, well-positioned – ability to address it.

To stand out, cite external sources credentialing your relevance and capability. Point to your expertise and track record — not broadly across your entire mission, but as specific to the project at hand as possible. You want donors to come away thinking “this is really important right now – and this group has a handle on how to get something done.”

When you’re at your most convincing, it’s apparent in your crystal clear words, sharp turns of phrase, and flashes of humor. It’s also evident in the absence of language that “just doesn’t sound like you.” The same is true for organizations. In making your case, how you say it is nearly as important as what you say. It’s not just about using an active voice or avoiding jargon and bureaucratic language – though both of those matter greatly.

It’s about developing a vocabulary and mode of expression reflecting your group’s unique

voice and personality. And it’s about spurning generic direct response language. Over time, the best writers develop an intuitive sense of what a group sounds like and what language and turns of phrase don’t “ring true.” (Reading your draft out loud is often the best way to test this.)

The name change test is another one I always recommend. Say you’ve written a Sierra Club appeal. Try changing each group reference to Greenpeace. If the letter still works pretty well, you haven’t written a Sierra Club appeal, you’ve written a generic environmental one. And that’s not good enough.

One of the central arguments of Kamala Harris’ campaign is that “elections are about the future.” The same is true about the most compelling nonprofit messages. Make sure the case you are making comes from a “what’s next” perspective.

Should it talk about your most relevant past achievements? Of course. But don’t cite your record in the abstract. Draw attention to it as concrete evidence of your — and, by extension, your reader’s — ability to have a positive impact on the challenge at hand.

What brings that “what’s next” point of view to life? Details. It’s challenging because often you have more information about what you’ve done than what you hope to do next. But being too vague about where you are heading can defeat the forward-looking energy of the case you’re making.

Look at your messaging. Make sure it leans into the future with a “what’s next” perspective. Because remember your audiences might respond to backward-looking “congratulations appeals” with a pat on the head. But genuine engagement only comes with the opportunity to help win the next battle.

Why not take a moment to review and tighten up your case for engagement. It will serve you well in the wild 4th quarter we have ahead of us.

My absolute favorite subject! Stephen Hitchcock, former Creative Director for MWD used to say, “It’s not entirely logical for someone to take the money they worked hard to hear and send it off to someone they’ve never met in the mail.” We get them to do that by inspiring them with emotion and helping them see the solution they can be a part of. Thanks for these timely reminders!