Eight Keys to Leading With Emotion

“Write with emotion and back it up with facts, not vice versa.”

– Kay Lautman

In her 1984 book Dear Friend, the legendary Kay Lautman advised writers to lead with

emotion supported by facts, not the other way around.

Back then, Lautman was operating on instinct and experience. Forty years later, we know

her wisdom is firmly rooted in behavioral science evidence about how our brains make

decisions.

Bernard Ross and Omar Mahmoud put it succinctly (emphasis added): “As influencers, we need to craft our messages for action to reach the subconscious as well as the conscious brain, with an emphasis on the former. The language of the subconscious brain is emotions, images, visuals, metaphors, story and music. The language of the conscious brain is text, logic, facts and numbers.”

But here’s the trick. The persuasiveness of our messages depends on how well we execute. Here are eight keys to effectively leading with emotion illustrated by concrete examples.

This memo includes over a dozen vivid examples from various groups, each evoking different emotions. But they all have one thing in common. They are all drawn from the very first sentence of a message.

A first draft often contains what I call “warm up language.” It’s the writer trying to get a grip on the topic. Don’t leave it in. Find the place where the message hits its emotional stride and make that the opening. Burying the lead is never a good idea, but it’s especially costly when what gets buried is the emotional connection with your audience.

Consider your organizational positioning before choosing emotions. Are you aligning emotional connections with your supporters’ perception of your group’s personality and voice? A few examples.

The National Audubon Society roots its emotional appeal in the deep love its audience has for birds, connecting with peoples’ personal identity as bird lovers.

“There is nothing else like birds. They are our most common wildlife. They are beautiful, they are resilient, and they are heroic. They touch our hearts and they fire up our imaginations.

Planned Parenthood, like other advocacy groups, often leans into anger and outrage. Their supporters aren’t looking for PPFA to be “warm and fuzzy” but rather to reflect the toughness and determination expressed in their “Care, no matter what” tagline.

“No one – not politicians or Supreme Court justices – will stop us from fighting for our right to control our bodies and our futures.”

To draw people in emotionally, Human Rights Watch uses “imagine,” one of the most powerful words in persuasive messaging. They cite examples of abuses that infuriate people and that the reader counts on HRW to confront.

“Imagine – being constantly watched using facial recognition software.

“Imagine – having to hide your sexual identity to avoid government harassment, even torture.

“Imagine – being forced to marry someone you don’t love. It’s happening to people across the world. We need your help to stop it.”

Guide Dog Foundation for the Blind uses the “imagine” device in a totally different way – to evoke empathy as opposed to anger.

“Close your eyes and imagine preparing for your day, walking to the corner, boarding a bus – all without opening your eyes.”

The emotions you seek to evoke must also match the moment, especially when competing feelings arise.

A good example of that dynamic is when a high-profile mass shooting occurs. Gun violence prevention groups face the challenge of balancing compassion for victims and survivors with outrage that politicians are still standing in the way of life-saving reforms.

The drill from gun rights politicians is familiar. They offer their “thoughts and prayers” to victims and survivors. Then they attack gun reform advocates who call for action to end the violence as being “political” at a time for mourning.

Pushing back against “thoughts and prayers” because they’re not linked to action can easily come across as being disparaging of religious belief. Here’s some language from Everytown for Gun Safety that artfully navigates this complicated emotional terrain.

“One of the best ways we can honor the lives lost is by taking action to end gun violence. Thoughts and prayers heal hearts, but elected officials change laws — and we need both to save lives.”

A key to the power of an emotional message is who delivers it. When the narrator can speak from personal experience, it can be especially evocative.

The executive director of the Trevor Project connects emotionally with a heartfelt personal memory.

“In 1992, I was 10 years old, living in suburban Boston, and questioning who I was, feeling alone, afraid and ashamed. I didn’t think anyone would ever understand or love me.”

And in this Make A Wish Foundation appeal, a father conveys in an easily relatable way the combination of anguish and hope a parent experiences when a child faces a serious illness.

“I remember thinking, if she can still ask for a wish like that, then she still feels the magic of childhood. And if I could find a way, some way, to make her wish come true, then maybe my own wish, that my daughter would recover, would come true, too.”

And this Doctors Without Borders example illustrate another important dynamic to keep in mind. Often a narrator closer to the action (e.g. a doctor in the field) can bring emotion to the fore more effectively than a more distant voice (e.g. a CEO back at headquarters).

“I will never forget Gloria’s face. When I greeted her at one of our Doctors Without Borders mobile clinics, she looked hopeless and exhausted.”

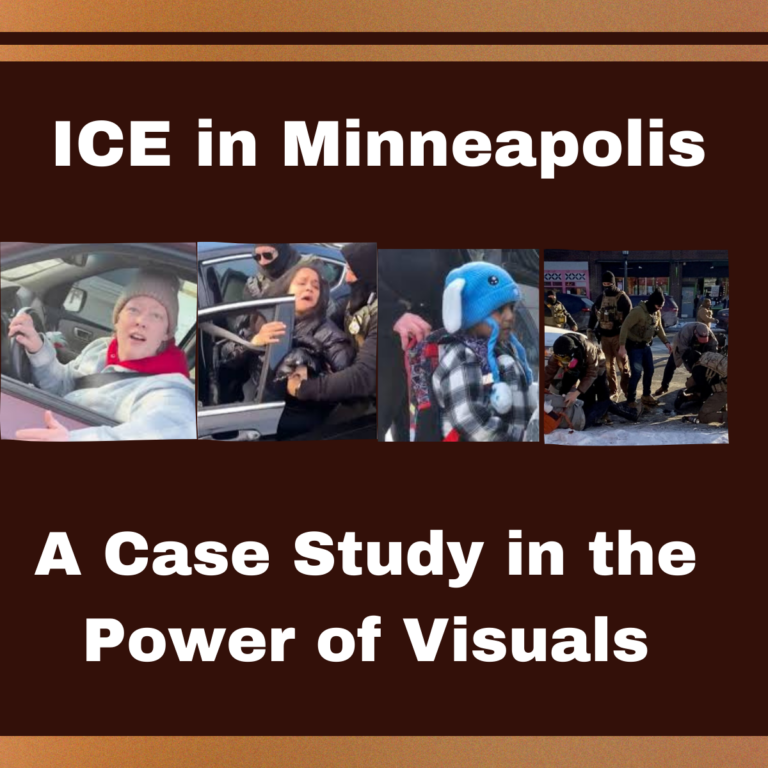

We all know that well-chosen photos can add to the emotional power of a message.

It is also true that the words we choose can do the same especially if we think and write in terms of visual storytelling.

Notice how this National Anti-Vivisection Society copy uses details like the color of the beagles’ eyes to aid your ability to picture a heartwarming scene which turns alarming with the visual image of the puppies being separated at birth.

“Imagine two adorable beagles, with dark brown eyes, separated at birth.”

And this language from The Audubon Society easily draws the reader in with visual details about flapping wings, subtle movements and vibrant colors.

“Hummingbirds are truly remarkable. With wings flapping up to 80 times per second, the bird’s subtle movements are beautiful, vibrant colors are mesmerizing.

The critical element in emotional storytelling isn’t jeopardy, it’s tension. We can certainly invoke emotions around preventing something bad or dangerous from happening. But emotional connection can also be achieved by encouraging people to seize a hard-earned opportunity for progress – as long as it’s one that depends on the donor to step forward to make it happen.

See this language from the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute that provides people with encouragement about their efforts to confront a dreaded disease.

“I have BIG NEWS for you. We are beating cancer.

“Every day, more people — from Maine to Connecticut and beyond – are surviving cancer.”

Taken too literally, the advice to lead with emotion and back it up with facts can set up a false choice. Facts have their place in the opening of your message if, but only if, they serve as triggers to an emotional reaction.

Here are two examples that do exactly that.

Parkinson’s Foundation: “In the time it takes you to read this letter, another person will be diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease (PD). And whether they live in (name city) or thousands of miles away, they will be searching for answers . . . support . . . hope.”

The Trevor Project: “Every 45 seconds a LGBTQ young person attempts suicide in the U.S. But our research shows that the risk decreases if they have just one supportive adult in their life.”

As I’ve expanded on in earlier posts, leading with strong emotions can either motivate or immobilize your audience. The factor that makes the difference is whether or not you provide the reader with a way to act in response to the emotional reaction.

This UNICEF message is a good example:

“Can you imagine what a mother feels when she knows her child is slowly succumbing to acute severe malnutrition? Watching her precious baby grow weaker and weaker, slowly shutting down for want of nutrition.

“Nyaweer can. “My child was malnourished, and I was so worried that my heart was weeping. I was terrified that he wasn’t going to survive…

“But he did thanks to the emergency nutrition he received in a UNICEF-supported clinic.”

Conclusion

Leading with emotion is one of the most powerful paths to persuasive messaging. Hopefully, the ideas and examples in this memo will make your efforts to evoke emotional reactions as effective as possible.

Great article. Thanks for these posts.