There’s a filter people instinctively use when evaluating a message. They ask themselves “Does what I am being told sound right? Does it ring true?”

Fail that test and you stand little chance of your audience choosing to engage with you and consider acting on your request.

It’s entirely possible for a message to be both true and unbelievable.

Put it this way: To be effective, your message not only has to be factually correct. It has to sound true to your audience. There’s a great word for that believability test: Verisimilitude

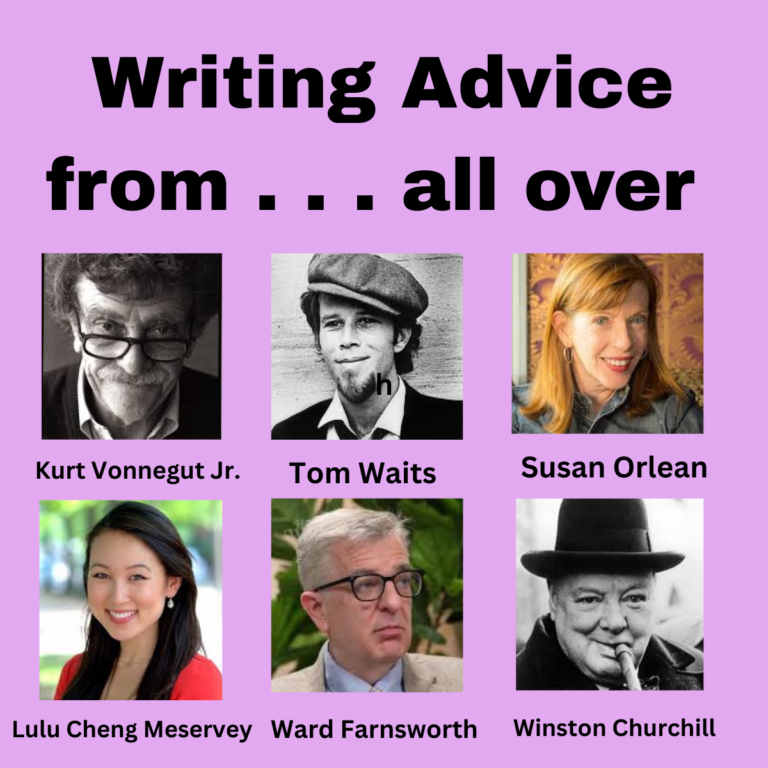

I first encountered this six syllable word for the appearance of being true in How to Write Powerful Fundraising Letters, a great copywriting book by Hershell Gordon Lewis.

Lewis was quite a character. He was a top-rated copywriter. But that’s not all. He was also a horror film screenwriter, claiming the title “the Godfather of Gore” for his bloody “splatter film” scripts. Oh and then there’s the three years he spent in prison after being convicted of fraud.

Lewis’ character aside, his fundraising books were always amazing. They featured full samples of actual fundraising letters followed by persuasive, no-holds-barred critiques of what he found good and, more often, bad in the copy.

Each time a new book came out, you’d read it with a touch of trepidation hoping something you wrote didn’t fall victim to Lewis’ colorful criticism. It happened to me once, but thankfully he used an ASPCA letter I’d written to draw a contrast with an unfortunate copywriter whose work fared less well.

In Lewis’ book (both literally and figuratively), the mortal sin was letters that lost their persuasiveness for lack of verisimilitude. So, let’s take a look at three ways your copy can fall into the verisimilitude trap and how to avoid doing so.

TRAP #1: Emphasizing a track record people aren’t aware of.

I’ve run into this issue when helping groups traditionally funded by major donors and foundations try to develop a small donor base. They have achieved a lot and can point to clear accomplishments. The problem: it’s all news to the potential donors they are approaching.

In that context, audiences tend to think “Wait a minute. If this group has done all this, why is this the first time I’m hearing about it? Either I’m not as clued in as I thought I was or this group is stretching the truth.”

That’s a dissonance people rarely resolve in the group’s favor.

- Back up your claims with outside credentialing.

- Scale back your language and avoid hyperbole.

- Let the reader off the hook for not knowing about you with language like “Honestly, we haven’t done enough to make people aware of our work.”

TRAP #2: Writing in a voice people find jarring.

Sometimes the issue isn’t what you’re saying as much as how you’re saying it. People have a sense of what your group sounds like – your voice and personality. The more intentional you have been about defining those traits, the clearer they are likely to be in the mind of your audience.

But, once you’ve established a clear voice and personality, you have to live it. And when you don’t, the believability of your message can suffer.

- Develop a clear sense of what kind of language fits and doesn’t fit your voice and personality.

- Use the “that doesn’t sound like us” test when writing and reviewing draft copy.

TRAP #3: Claiming a “first in the field” position another group owns.

Here’s another form of overreach that can sink the believability of your message: claiming a mantle within your subject matter arena that people already attribute to another group.

When people engage on an issue, they look for a group that will be their best vehicle for taking action. But “top in our field” or “the best step you can take” positioning has to be earned, not just claimed.

- Don’t raise the “who’s the best on this” standard unless you can claim it.

- Carve out a specific part of work on the overall issue where you can credibly claim a unique role.

Both ethically and in terms of protecting your long-term reputation, it’s always essential to make sure everything in your message is true.

But you have to stay alert to the second crucial test: Do the things you’re asserting and the role you’re claiming also ring true? By making sure you can answer that question in the affirmative, you can avoid the lack of verisimilitude pitfall.