Properly applied, behavioral science can play a compelling role strengthening the persuasiveness of our messages. Today let’s discuss specific concepts drawn from books by two of my favorite writers on the science of persuasion.

And since the authors deal primarily with commercial marketing, I’ve included specific examples of how each notion might be applied to our nonprofit messaging.

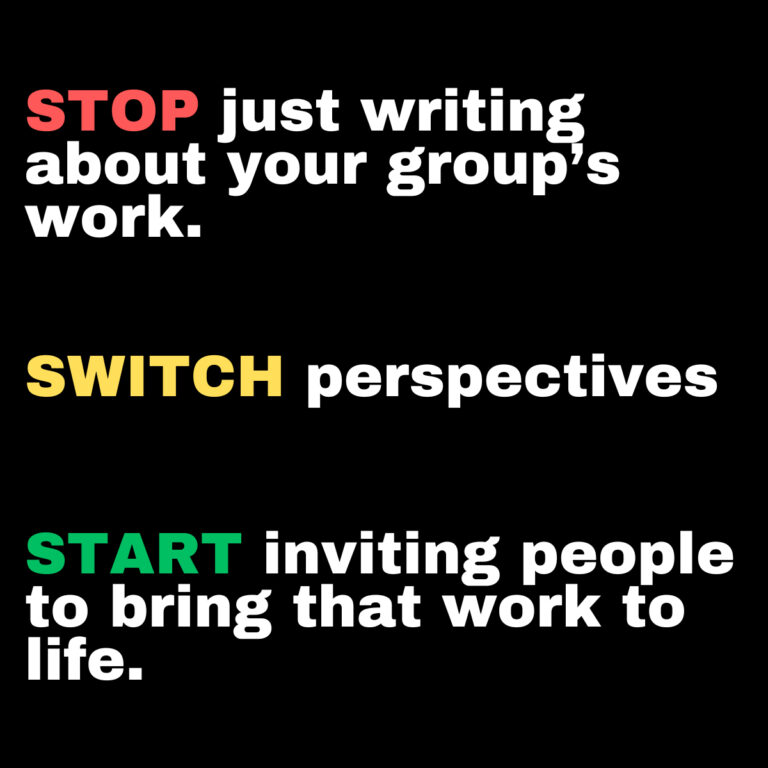

Word Choice, Framing and Concreteness

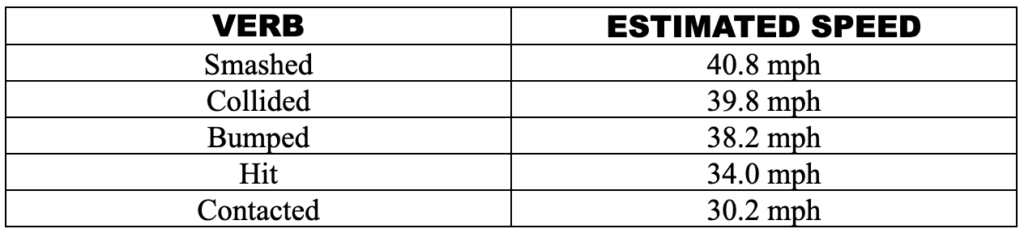

In his book, Richard Shotton delves into the significant impact of word choice. He describes a research study in which participants were shown a video of a car accident and asked to guess how fast the cars were going.

But there was variation in one word – the verb used to describe the situation. Here are the five verbs and the average MPH speed that participants guessed.

Those who were asked the “smashed” question thought the cars were travelling 27% faster than those who were asked the “contacted” version. Why? Because the language helped frame the participants’ mental picture of the accident.

Bonus Insight: In his book, Shotton also presents research showing that concrete phrases (fast car, skinny jeans, cashew nut, money in the bank) are ten times more likely to be retained than abstract phrases (innovative quality, trusted provenance, central purpose, ethical vision.)

Neuroscience and Surprising the Brain

Surprise is an emotion whose power we invoke less frequently than we should. As Dooley notes, neuroscientists are learning more and more about how our brains react to unexpected events.

One key dynamic is that our brains work hard to predict what will happen next.

Dooley cites a wonderful spoken word illustration of this process by Scientific American’s Steve Mirsky:

“While I’m talking, you’re not just passively listening. Your brain is also busy at work guessing the next word that I will sa . . .vor before I actually speak it. You thought I was going to say “say,” didn’t you? Our brains actually consider many possible words – and their meanings – before we’ve heard the final word in quest . . . of being understood.”

As I hope these examples make clear, if properly used, behavioral science can powerfully contribute to the persuasiveness of our nonprofit communications. In future memos, I will explore additional behavioral science concepts and how to apply them in our space.